Reflecting on Secretomotor Phenomenon: Witnessing the Quiet Power of Tears

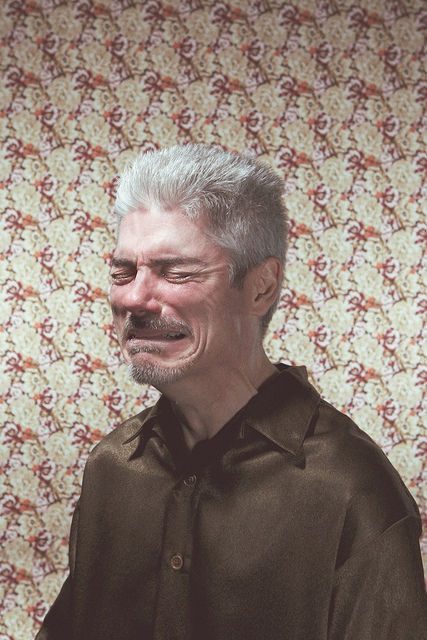

In 2013, just a few years into my art practice, I made Secretomotor Phenomenon. The series is simple in description but was anything but simple to create or to experience. At its heart, it’s a collection of portraits of people crying. No elaborate sets, no costumes, no narrative cues. Just faces, tears, and a kind of raw openness that still humbles me when I look back on it.

I’ve always been interested in the parts of life that feel hidden. The moments that we protect out of fear, embarrassment, or the sense that they’re “too much.” Even early in my work, I felt pulled to document the things that don’t make it into most photographs. At that time, I was thinking a lot about how public vulnerability had become performative in certain ways. We can share everything online, yet many emotions, especially grief, sadness, and unguarded crying, remain almost taboo. It felt like in an age where nudity was commonplace, tears were somehow more intimate.

One of the most frequent questions I’ve been asked about Secretomotor Phenomenon is: “How did you make these people cry?” The truth is, I didn’t. I didn’t have to. Instead, I created a space where they felt safe enough to let their emotions surface on their own. The studio was quiet. We would talk a little, or sometimes not at all. There was no expectation or timeline. The premise was simple: if you feel something, let it happen.

The experience of being in front of so many people in those moments was incredibly emotional for me, too. As the photographer, I wasn’t just an observer. I was a witness. And witnessing is different than watching. Witnessing means holding space for someone else’s reality without needing to fix it or look away. It means allowing yourself to be affected by their humanity, even when it’s uncomfortable.

I remember moments when the quiet was so complete that the only sound was breathing and the occasional movement in the chair. There were tears that came gently, almost out of nowhere, and tears that arrived with visible effort, like something old being finally released. Some people apologized for crying, as if their vulnerability was an inconvenience. Others sat silently for a long time and simply nodded when they were ready to stop.

In many ways, the process of making this work mirrored the themes I was trying to explore. The tension between public and private, the complexity of emotional expression, and the invisible barriers we put between ourselves and others. Photographing someone crying isn’t about documenting sadness. It’s about documenting a moment of truth. And truth is never one-dimensional.

One of the reasons I named the series Secretomotor Phenomenon was to call attention to the paradox of crying as both a physiological process and a profoundly human gesture. The clinical term feels so detached, like crying is just another reflex. But when you look at someone’s face as they shed tears, you know it’s anything but mechanical. It’s a glimpse into the complexity of being alive.

Looking back, I see Secretomotor Phenomenon as a turning point. It taught me that the camera can be both a shield and a bridge. Holding a lens doesn’t have to mean creating distance. Sometimes it means creating a container where something real can unfold. It also shaped how I approach all of my work, whether it’s a series about perception like Who Are We. or an exploration of the body like Illusions of the Body.

Even now, more than a decade later, I still think about those sessions. About how much courage it took for each participant to let me see them in that state. About how much it asked of me to remain present, to not rush or intellectualize, but to simply be there.

When people encounter this series today, whether they find it through my art archive or stumble on it while exploring other projects, my hope is that they feel the same reverence I did. That it feels like a reminder that vulnerability is not weakness, and that witnessing someone else’s truth can be an act of care.