Reflecting on Illusions of the Body: Going Viral and the Lessons That Followed

In 2013, I made Illusions of the Body to challenge the narrow definitions of beauty that dominate the media. We all know that the images we see in magazines and online are the “best” versions of people, carefully selected, staged, and often retouched, yet we still compare ourselves against those impossible standards. What we rarely see is the contrast. What would happen if we saw the “beautiful” photo right next to another image of that same person, taken just moments later, that feels less conventionally flattering? That contrast, I believed, could help shift the way we think about our bodies.

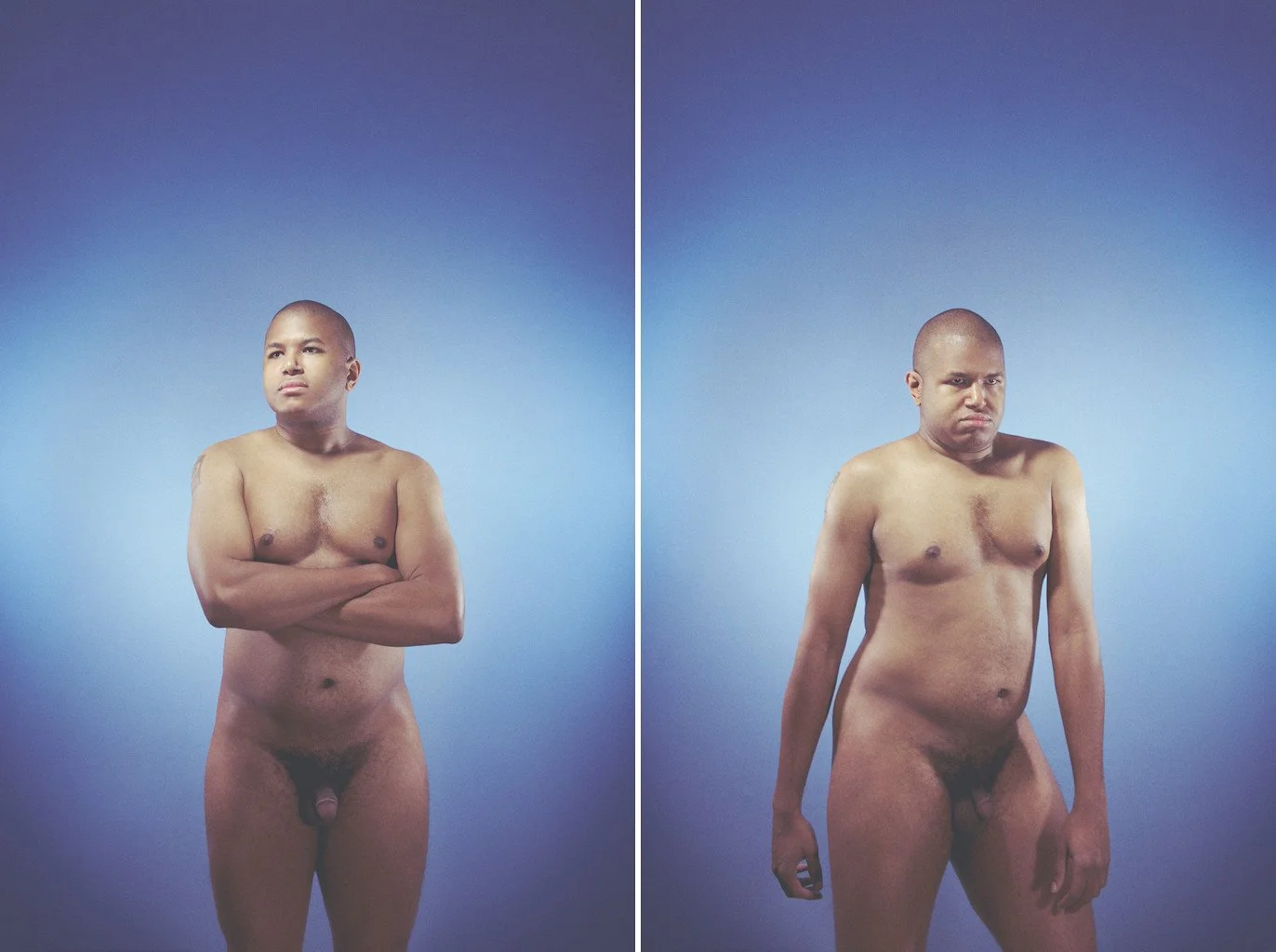

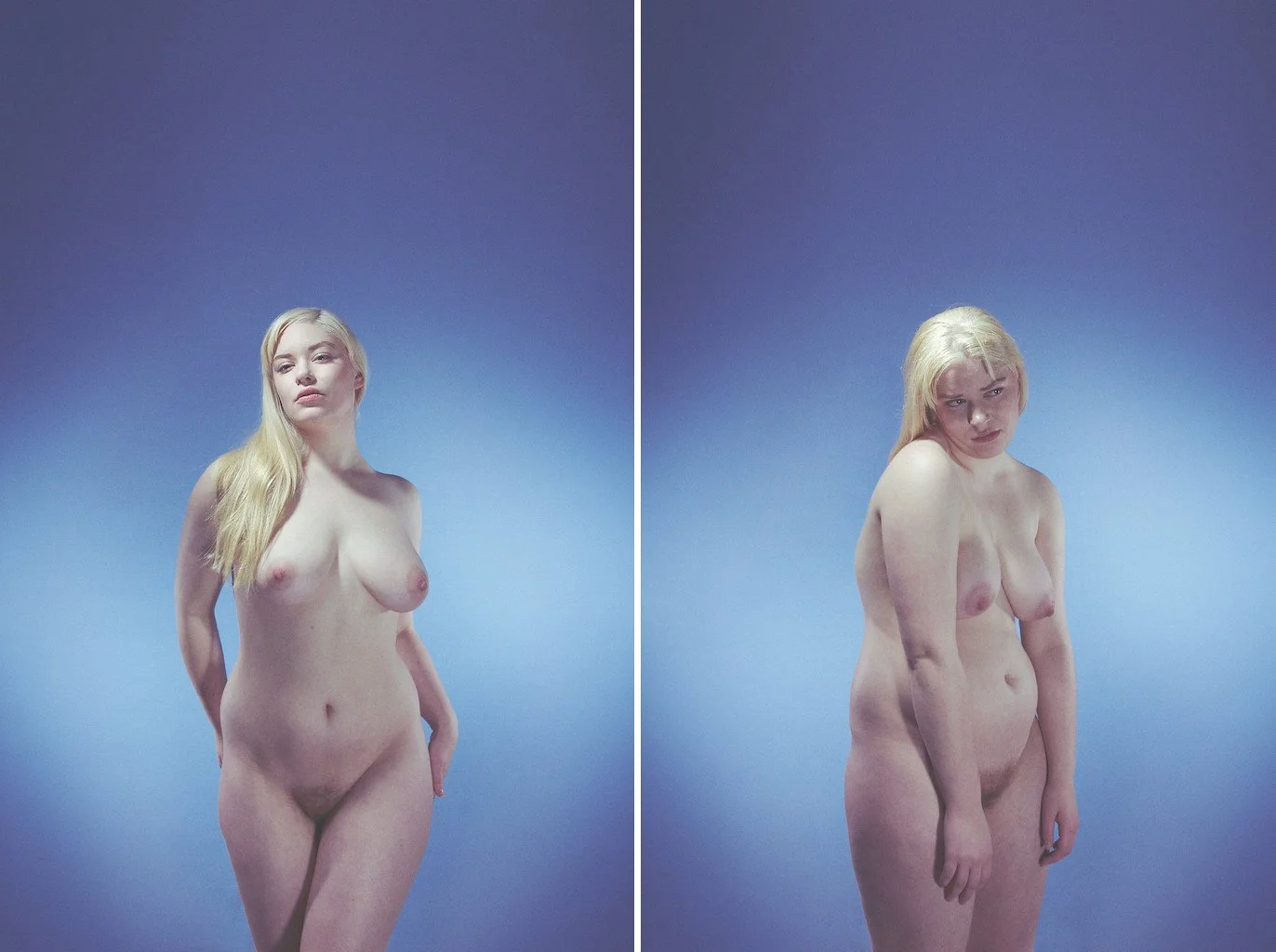

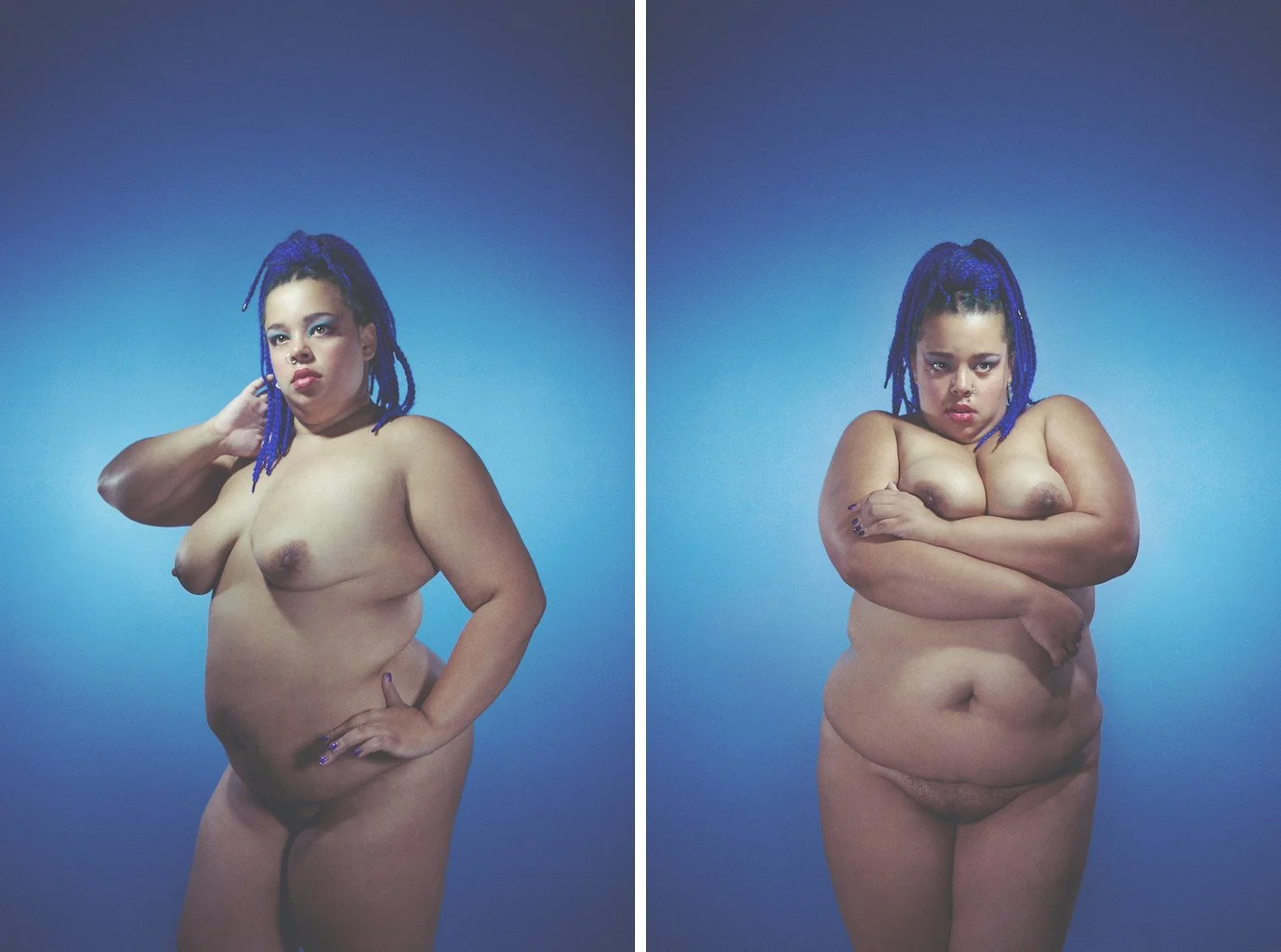

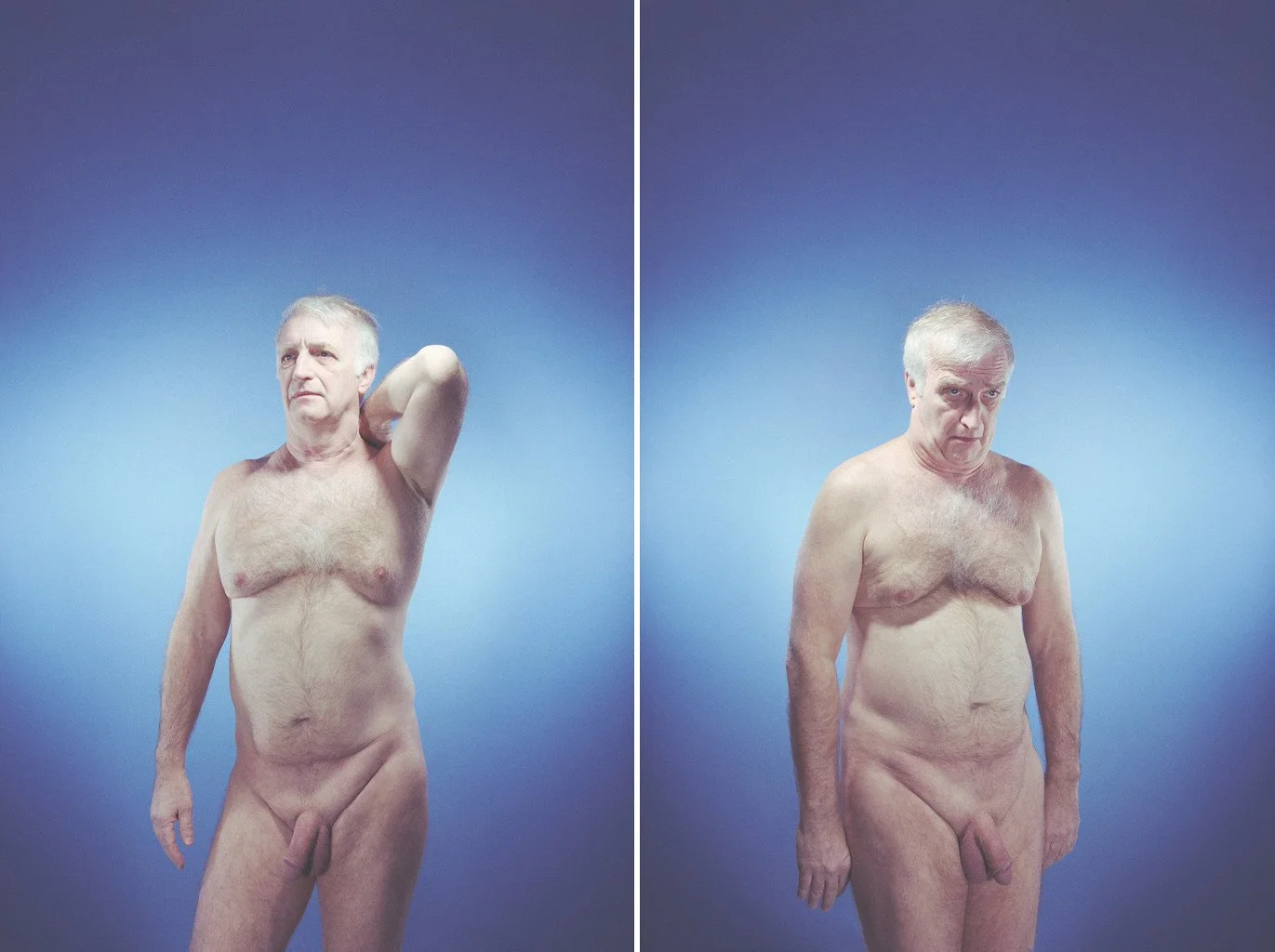

Each participant was photographed twice in quick succession. The lighting, camera angle, and position never changed. What shifted was the person, their orientation toward the camera, how the light hit their face if they turned slightly, the way their body’s relationship to the lens altered its shape. Sometimes posture played a role, sometimes it was the smallest change in facial angle or body rotation. Those subtle shifts created drastic differences in how the same body was perceived. I worked with people of different body types, ethnicities, and genders to underline that there is no “normal” body, only the diversity that already exists all around us.

When the series was released, I had no idea what would happen next. Illusions of the Body went viral almost overnight. The images were shared internationally, picked up by major publications, and sparked countless conversations online. The project resonated with people in a way I couldn’t have predicted. While it was thrilling to see the work spread so far, the experience also brought unexpected pressures. There was a moment where I wondered if I would need to keep creating similar work to maintain that momentum. If the next project wasn’t as widely shared, did that mean it wasn’t as good?

The visibility brought incredible opportunities, though. I was able to self-publish a book of the series, and both printings sold out. Interestingly, most of the copies went overseas, which revealed a lot about cultural differences in attitudes toward nudity. In the United States, nudity often sparks controversy or is immediately sexualized, while in much of Europe, it is approached with a greater sense of openness and normalcy. That difference was reflected in how the work was received.

The process of making Illusions of the Body was just as memorable as its reception. Every person who participated gave their time and their trust. The project was entirely a labor of passion, mine and theirs. I didn’t set out with a grand plan, I just wanted to create something honest, something that might help people see themselves in a kinder light. That sincerity, I think, is part of why it resonated so widely.

Looking back, Illusions of the Body was a pivotal moment in my career. It reinforced my interest in work that challenges cultural norms and encourages viewers to question what they think they know. It also taught me a valuable lesson about success. Virality is fleeting. What matters most is what happens during the making of the work, the intention, the process, the connection. A viral response is not a reliable measure of value. Since then, I’ve made work that I believe is stronger, more nuanced, and more thought-provoking, even if it hasn’t received the same level of attention. That disconnect challenged me to define success on my own terms, not by metrics of visibility but by the integrity of the work itself.

When people encounter this series today, my hope is the same as it was in 2013: that it prompts a moment of recognition. That we all look at our own bodies, and the bodies of others, with a little more kindness. The human body is strange, beautiful, and endlessly changeable. That’s worth celebrating. And as we veer further into a cultural climate shaped by rising conservatism, image obsession, and anti-fat rhetoric, fueled by the normalization of drugs like Ozempic and the resurgence of thinness as a moral ideal, this kind of visual counter-narrative feels more urgent than ever. We need reminders that our bodies don’t need to conform to be valid.